DNS Encryption (DoH, DoT) – What It Is, and Why Do Big Companies Argue About It?

There were a lot of big words on the topic of DNS encryption lately. With Google, Mozilla and Cloudflare on one side, and government regulators and internet service providers on the other, it is clear there is a strong disagreement on the vision of how a safer and more secure future internet should look – or at least on the steps we should take toward making it. But what is DNS encryption and why is it a topic followed by so much controversy?

And here is a handy table of contents to make finding the information you need easier:

- What is DNS?

- Why would someone want to change something so commonly used?

- What is DNS encryption?

- Why does Google want to make everyone encrypt their DNS requests? Why do governments and telecoms (among others) oppose it?

What is DNS?

In short – DNS is a machine that translates domain name-based addresses into number-based IP addresses. All of the internet-connected devices in the world communicate by addressing each other by number-based IP addresses. When looking for a website or a service, in order to translate www.domain.me into 192.124.249.64 we ask for the help of Domain Name Resolver – or DNS, for short. You can read much more about DNS and how it works in our article on the subject, but the purpose of DNS is to be a fast-responding machine we can trust to point us to the right address each time we ask for a domain name.

Why would someone want to change something so commonly used?

One concern for the proponents of more private DNS technologies is that, even when your traffic is private – your DNS queries are not. This means your internet provider knows what websites you are visiting and when, and that they can do all sorts of things with this data – from creating usage profiles to engineer a system more suitable to their users’ needs to protecting you from visiting harmful websites to outright selling this data to companies that want to target ads based on people’s browsing profiles. Even if they do not want to sniff your traffic, they are often legally bound to, as many countries in the world have laws that force them to block people from visiting certain “dangerous” websites.

The other concern is that the internet, in its primitive form, was not created to be too safe. DNS is a remnant of these old times, and having the “last mile” of internet traffic unencrypted leaves some space for clever hackers to combine “man in the middle” attacks with other techniques to hijack traffic for phishing purposes. In addition to that, the way DNS currently works makes it a tool in UDP-based amplification attacks, where hackers abuse the workings of DNS servers to amplify the impact of malicious traffic.

What is DNS encryption?

To truly complete the end-to-end eavesdropping prevention, a tiny little step called SNI encryption is required on top of DoH. You can read more about it in this article by Cloudflare.

DNS encryption is a way to encrypt DNS traffic between the user and their DNS server. By encrypting and wrapping this traffic, DNS spoofing and man-in-the-middle attacks are prevented, and eavesdropping on this communication is prevented.

There are many competing ways to encrypt DNS traffic. DNS over TLS (DoT) and DNS over HTTPS (DoH) are two of the most popular and they are not unlike the ways we already use to encrypt the rest of our internet communication (HTTPS and TLS). Firefox already supports DoH, and Google supports both DoT and DoH. The way they work is similar, although there are strong opinions among internet security experts on what the port specific to each of them can mean for the future of online safety and privacy. DoT also makes it possible for ISPs to force you to use (their) local DNS resolver, with all the good and bad sides that come with it.

Yes and no. DNSSEC protects you from man-in-the-middle and spoofing attacks (read more about it on our DNSSEC guide). It is an important tool in securing traffic, but it does not (and was never made to) prevent ISPs from tracking your DNS requests.

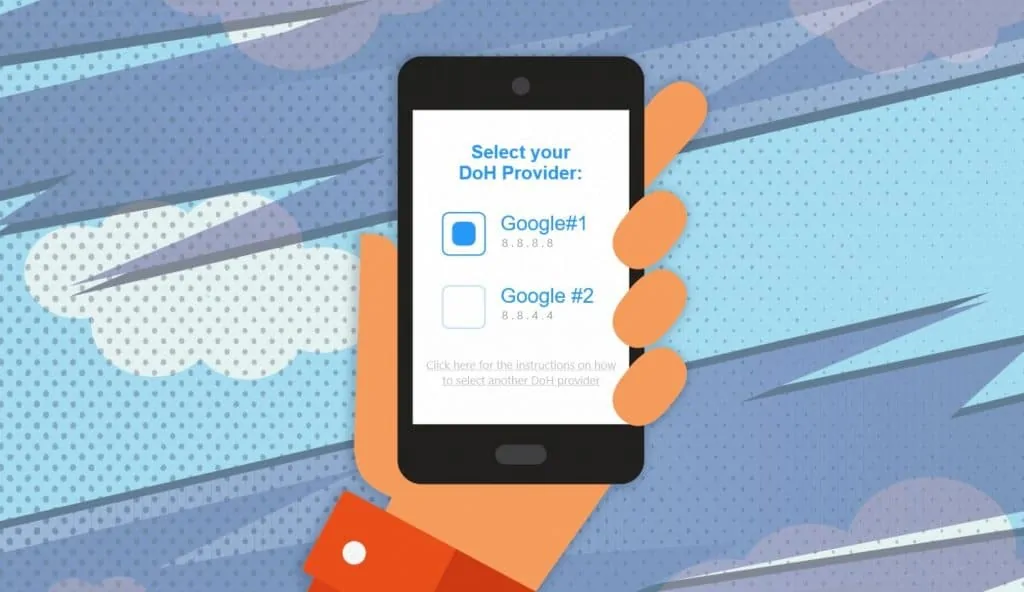

Many DNS servers already support encrypted communication, but enabling this encryption for the end-user (especially if they want to do it system-wide) requires them to have knowledge about proxy services, resolver settings, daemon services and a couple of other things that make the average user’s head spin around. Having all of your DNS queries encrypted (if you are not using a VPN service) is hard at this time, but things are looking like they are going to change. Firefox was the first of the big names to make switching to encrypted DNS an extremely user-friendly process. For these efforts, ISPA – the British body representing Internet providers – nominated them for the “Internet Villain of the Year” award. Clearly, there are two sides to this story.

Why does Google want to make everyone encrypt their DNS requests? Why do governments and telecoms (among others) oppose it?

Remember when we said that encrypting and wrapping your DNS traffic prevents eavesdropping of your DNS communication? Well – add a little “sort of” to that. The communication between you and your DNS server is truly encrypted, but there is no technical limitation to prevent your DNS provider from logging your requests and doing whatever they like with them. The privacy of your online communication is something that is mathematically impossible to compromise in every step between you and the server you are communicating with – with the exception of your DNS. There – it still rests on little more than a pinky promise that your DNS provider is not going to log and process your traffic data. It is, however, up to you to choose whose pinky promise you believe the most, and you can pretty much be sure that the weakest part of your privacy protection is still someone you trust.

Google has made great things for the internet privacy by promoting encrypted communication with websites, making the internet a better place in the process. It is hard to deny it, and it is hard to deny the fact that the DNS encryption, as a final brick in this wall, is a good thing in principle. The problem for the opponents of their way of doing it is the intent to completely avoid the confines of the current ecosystem, breaking some of the already established important things in the process.

With new Android updates on the horizon and Chrome browser closely following, Google is going to make it easy to switch to an encrypted DNS server, and you can be sure that the easiest server to switch to is going to be one owned by them. This makes ISPs completely unable to monitor the traffic. It removes their ability to log and analyse users’ requests (be it to optimize their infrastructure or to monetize your browsing habits), but also renders them unable to filter traffic. DNS blocking is something they argue creates a safer space for their users by preventing them to access the most malicious content, but also something they are currently legally bound to do – in cases of websites containing child pornography and other criminal content. “More secure”, in this case, might not also mean “safer”.

Without the ability to apply DNS blocking, the filtering has to be done on the device level, and the work on documenting and standardizing ways to do it is not even nearly done. This leaves a gap between what the laws say should be done and what could actually be done in these cases.

There is also raising concern that moving a significant portion of traffic to encrypted DNS requests will create a more monopolistic market for aggregate user data. With the largest web search provider, a dominant web browser, the most popular analytics software, and a top mobile operating system in their ecosystem, it is easy for Google to give up on data collected by DNS queries. They already collect zero data from the non-encrypted DNS queries. For many ISPs, these queries are the main, if not the only source of reliable user data. Google has always had their business interests strategically aligned with making the internet a better place, but there is an evident additional incentive in this case. Dominating another foundation of the internet is certainly not going to lose them money. On the other hand – the question about the right to own our own digital trace can be raised, especially when the way for ISPs to keep tracking us is to keep the online communication less secure (even if not necessarily less safe).

Each side has a point and none of them are completely right. The battle for (and against) the current push of DNS encryption is a struggle for power between large multinational companies with strong political influence, and it will probably be settled as such. We can only hope that will mean safer, more secure and ultimately better internet for all of us.